Node.js and the new web front-end

Front-end engineers have a rather long and complicated history in software engineering. For the longest time, that stuff you sent to the browser was “easy enough” that anyone could do it and there was no real need for specialization. Many claimed that so-called web developers were nothing more than graphic designers using a different medium. The thought that one day you would be able to specialize in web technologies like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript was laughable at best – the UI was, after all, something anyone could just hack together and have work.

JavaScript was the technology that really started to change the perception of web developers, changing them into front-end engineers. This quirky little toy language that many software engineers turned their noses up at became the driving force of the Internet. CSS and HTML then came along for the ride as more browsers were introduced, creating cross-browser incompatibilities that very clearly defined the need for front-end engineers. Today, front-end specialists are one of the most sought after candidates in the world.

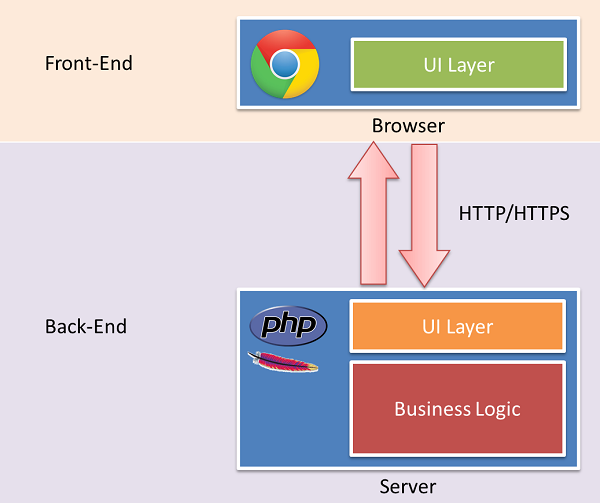

The two UI layers

Even after the Ajax boom, the front-end engineer was seen as primarily working with technologies inside of a browser window. HTML, CSS, and JavaScript were the main priorities and we would only touch the back-end (web server) in order to ensure it was properly outputting the front-end. In a sense, there were two UI layers: the one in the browser itself and the one on the server that generated the payload for the browser. We had very little control over the back-end UI layer and were often beholden to back-end engineers’ opinions on how frameworks should be put together – a world view that rarely took into consideration the needs of the front-end.

In this web application architecture, the UI layer on the browser was the sole domain of front-end engineers. The back-end UI layer was where front-end and back-end engineers met, and then the rest of the server architecture was where the guts of the application lived. That’s where you’d find data processing, caching, authentication, and all other pieces of functionality that were critical to the application. In a sense, the back-end UI layer (often in the form of templates) was a thin layer inside of the application server that only served a front-end as incidental to the business logic it was performing.

So the front-end was the browser and everything else was the back-end despite the common meeting ground on the back-end UI layer. That’s pretty much how it was until very recently.

Enter Node.js

When Node.js was first released, it ignited a level of enthusiasm amongst front-end engineers the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the term “Ajax” was first coined. The idea of writing JavaScript on the server – that place where we go only when forced – was incredibly freeing. No longer would we be forced to muddle through PHP, Ruby, Java, Scala, or any other language in addition to what we were doing on the front-end. If the server could be written in JavaScript, then our complete language knowledge was limited to HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to deliver a complete web application. That promise was, and is, very exciting.

I was never a fan of PHP, but had to use it for my job at Yahoo. I bemoaned the horrible time we had debugging and all of the stupid language quirks that made it easier to shoot yourself in the foot than it should be. Coming from six years of Java on the server, I found the switch to PHP jarring. I believed, and still do believe, that statically typed languages are exactly what you want in the guts of your business logic. As much as I love JavaScript, there are just some things I don’t want written in JavaScript – my shopping cart, for example.

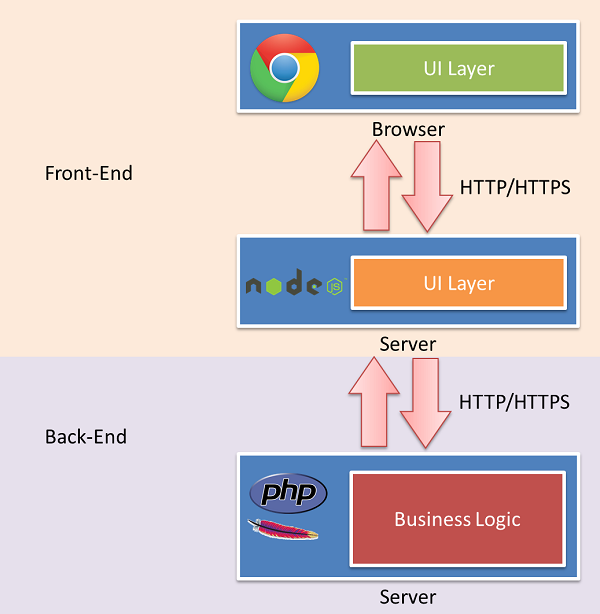

To me, Node.js was never about replacing everything on the server with JavaScript. The fact that you can do such a thing is amazing and empowering, but that doesn’t make it the right choice in every situation. No, to me, I had a very different use in mind: liberating the back-end UI layer from the rest of the back-end.

With a lot of companies moving towards service-oriented architectures and RESTful interfaces, it now becomes feasible to split the back-end UI layer out into its own server. If all of an application’s key business logic is encapsulated in REST calls, then all you really need is the ability to make REST calls to build that application. Do back-end engineers care about how users travel from page to page? Do they care whether or not navigation is done using Ajax or with full page refreshes? Do they care whether you’re using jQuery or YUI? Generally, not at all. What they do care about is that data is stored, retrieved, and manipulated in a safe, consistent way.

And this is where Node.js allows front-end engineers a lot of power. The back-end engineers can write their REST services in whatever language they want. We, as front-end engineers, can use Node.js to create the back-end UI layer using pure JavaScript. We can get the actual functionality by making REST calls. The front-end and back-end now have a perfect split of concerns amongst the engineers who are working on those parts. The front-end has expanded back onto the server where the Node.js UI layer now exists, and the rest of the stack remains the realm of back-end engineers.

No! Scary!

This encroachment of the front-end into what was traditionally the back-end is scary for back-end engineers, many of whom might still harbor resentment against JavaScript as a “toy” language. In my experience, it is exactly this that causes the organizational disagreement related to the adoption (or not) of Node.js. The back-end UI layer is disputed land between the front-end and back-end engineers. I can see no reason for this occurring other than it’s the way things always have been. Once you get onto the server, that is the back-end engineer’s responsibility. It’s a turf war plain and simple.

Yet it doesn’t have to be that way. Separating the back-end UI layer out from the back-end business logic just makes sense in a larger web architecture. Why should the front-end engineers care what server-side language is necessary to perform business-critical functions? Why should that decision leak into the back-end UI layer? The needs of the front-end are fundamentally different than the needs of the back-end. If you believe in architectural concepts such as the single responsibility principle, separation of concerns, and modularity, then it seems almost silly that we didn’t have this separation before

Except that before, Node.js didn’t exist. There wasn’t a good option for front-end engineers to build the back-end UI layer on their own. If you were building the back-end in PHP, then why not also use PHP templating to build your UI? If you were using Java on the back-end, then why not use JSP? There was no better choice and front-end developers begrudgingly went along with whatever they had to use because there were no real alternatives. Now there is.

Conclusion

I love Node.js, I love the possibilities that it opens up. I definitely don’t believe that an entire back-end should be written in Node.js just because it can. I do, however, strongly believe that Node.js gives front-end engineers the ability to wholly control the UI layer (front-end and back-end), which is something that allows us to do our jobs more effectively. We know best how to output a quality front-end experience and care very little about how the back-end goes about processing its data. Tell us how to get the data we need and how to tell the business logic what to do with the data, and we are able to craft beautiful, performant, accessible interfaces that customers will love.

Using Node.js for the back-end UI layer also frees up the back-end engineers from worrying about a whole host of problems in which they have no concerns or vested interest. We can get to a web application development panacea: where front-end and back-end only speak to each other in data, allowing rapid iteration of both without affecting the other so long as the RESTful interfaces remain intact. Jump on in, the water’s fine.

Disclaimer: Any viewpoints and opinions expressed in this article are those of Nicholas C. Zakas and do not, in any way, reflect those of my employer, my colleagues, Wrox Publishing, O'Reilly Publishing, or anyone else. I speak only for myself, not for them.