Hidden performance implications of Object.defineProperty()

I’ve recently been working on a project to port Espree[1], the parser that powers ESLint[2], to use Acorn[3]. In so doing, I ran into an interesting performance problem related Object.defineProperty(). It seems that any call to Object.defineProperty() has a nontrivial negative affect on performance in V8 (both Node.js and Chrome). An investigation led to some interesting results.

The problem

I noticed the problem the first time I ran ESLint’s performance test, which showed a 500ms slowdown using the Acorn-powered Espree. Using the current version of Espree (v2.2.5), the ESLint performance test always completed in about 2500ms (you can run this yourself by cloining the ESLint repository and running npm run perf). When I switched to use Acorn-powered Espree, that time ballooned to just over 3000ms. A 500ms increase is much too large of a change and would undoubtedly affect ESLint users in a significant way, so I had to figure out what was taking so long.

The investigation

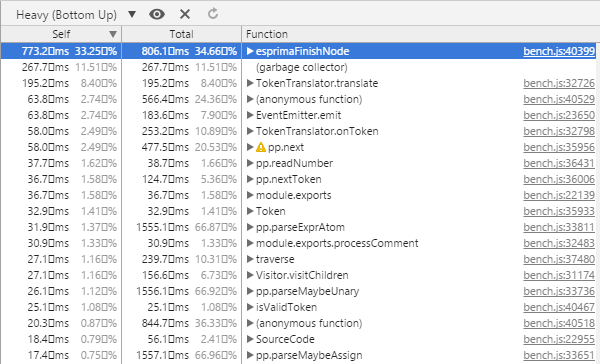

To do that, I used ESLint’s profiling command (npm run profile) to run ESLint through Chrome’s profiler. When I did that, something immediately jumped out at me.

As you can see, the function esprimaFinishNode() was taking up over 33% of the run time. This function augments the generated AST nodes from Acorn so that they look more like Esprima AST nodes. It took me only a minute to realize that the only out-of-place operation in that function involved Object.defineProperty().

Acorn adds nonstandard start and end properties to each AST node in order to track their position. These properties can’t be removed because Acorn uses them internally to make decision about other nodes. So instead of removing them, Espree was setting them to be nonenumerable using Object.defineProperty(), like this:

Object.defineProperty(node, "start", { enumerable: false });

Object.defineProperty(node, "end", { enumerable: false });

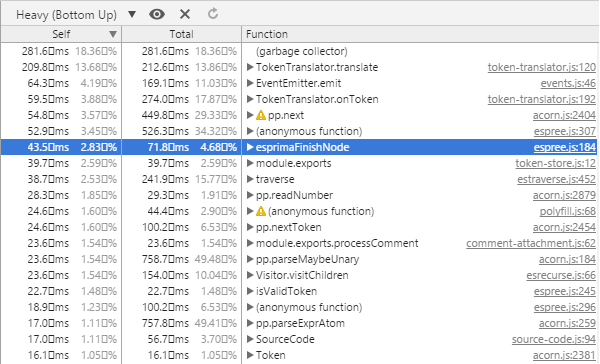

By making these properties nonenumerable, the output of JSON serialization would match that from Esprima and anyone using for-in loop would be unaffected. Unfortunately, this was the very thing that caused the performance problem. When I commented out those two lines, the profile run looked very different:

All of a sudden, esprimaFinishNode() was no longer where the most time was spent, accounting for less than 5% (owning less than 3%). The different was the two calls to Object.defineProperty().

Digging in deeper

I really wanted to make start and end nonenumerable, so I tried several alternatives to using Object.defineProperty() in esprimaFinishNode().

The first thing I did was use Object.defineProperties() to define both properties instead of two separate calls to Object.defineProperty(). My thinking was that perhaps each call to Object.defineProperty() was incurring a performance penalty so using one function call instead of two could cut that down. This made no change at all, and so I concluded the reason for the slowdown was not the number of times Object.defineProperty() was called, but rather, the fact that it was called at all.

Remembering some of the information I read about V8 optimization[4], I thought this slowdown might be the result of the object changing shape after it was defined. Perhaps change the attributes of properties was enough to change the shape of the object in V8, and that was causing a less optimal path to be taken. I decided to this theory.

The first test was the original code, which loosely looked like this:

// Slowest: ~3000ms

var node = new Node();

Object.defineProperty(node, "start", { enumerable: false });

Object.defineProperty(node, "end", { enumerable: false });

As I mentioned before, this was about 3000ms in the ESLint performance test. The first thing I tried was to move Object.defineProperty() into the Node constructor (which is used to create new AST nodes). I thought that perhaps if I could better define the shape inside the constructor, I’d avoid the late penalties of changing the shape long after its creation. So the second test looked something like this:

// A bit faster: ~2800ms

function Node() {

this.start = 0;

this.end = 0;

Object.defineProperty(node, "start", { enumerable: false });

Object.defineProperty(node, "end", { enumerable: false });

}

This did result in a performance improvement, dropping the ESLint performance test from 3000ms to around 2800ms. Still slower than the original 2500ms, but moving in the right direction.

Next, I wondered if creating the property and then making it enumerable would be slower than just using Object.defineProperty() to both create it and make it enumerable. Thus, I took another stab at it:

// Faster: ~2650ms

function Node() {

Object.defineProperties(this, {

start: { enumerable: false, value: pos, writable: true, configurable: true },

end: { enumerable: false, value: pos, writable: true, configurable: true }

});

}

This version brought the ESLint performance test down even further, to around 2650ms. The easiest way to get it back down to 2500ms? Just make the properties enumerable:

// Fastest: ~2500ms

function Node() {

this.start = 0;

this.end = 0;

}

Yes, it turns out not using Object.defineProperty() at all is still the most performant approach.

Takeaways

What was most surprising to me is that there was basically no truly efficient way to make properties nonenumerable, especially when compared against simply assigning a new property onto this directly. This investigation showed that if you must use Object.defineProperty(), it’s better to do so inside of a constructor than outside. However, where performance is a consideration, it seems best to avoid using Object.defineProperty() at all.

I’m thankful that I had the ESLint performance test, which runs ESLint on a fairly large JavaScript file, to be able to narrow this issue down. I’m not sure an isolated benchmark would have revealed the extent to which this was a problem for ESLint.

References

- Espree (github.com)

- ESLint (github.com)

- Acorn (github.com)

- What’s up with monomorphism?

Disclaimer: Any viewpoints and opinions expressed in this article are those of Nicholas C. Zakas and do not, in any way, reflect those of my employer, my colleagues, Wrox Publishing, O'Reilly Publishing, or anyone else. I speak only for myself, not for them.